Northern Ostrobothnia Museum has acquired an object for its collections, the story of which is like a lesson about the cultural history of the 17th-18th centuries. It is a silver jug from the year 1697 given by merchant and alderman Klaus Jenderjan (1650–1704) to his wife Katarina Heikintytär (d. 1737) as a morning gift. The item has been purchased from a collector from Oulu.

Jenderjan’s silver jug in the museum’s main exhibition. Photo: Inka Lohvansuu

Morning gift was the widow’s social security

The silver and partly gilded jug was made by silversmith and royal purveyor Johan Nützel (operated in 1676–1715) from Stockholm. The text Claes Jenderrian Charin hinrich’s Dotter Jenderian’s A: 1697 is engraved on the lid in the form of a circle. The diameter of the base of the jug is 14 cm and its weight is 1430 grams. On the bottom of the silver dish are the manufacturing marks: alderman’s serrated staff, the year letter G and the maker’s mark N. Above the letters is Stockholm’s city stamp: St. Erik’s crowned head.

It was customary that the morning gift (morgongåva in Swedish) was given to the bride after the wedding night. It was the wife’s statutory protection against widowhood. Katarina Heikintytär’s morning gifts probably included more than the silver jug, possibly land as well. Katarina already had one child to support at the time of the marriage. In addition, the person in question was a wealthy merchant, so presumably the morning gift reflected that.

The unbelievable fortune of the Jenderjans

Klaes Jenderjan drowned in 1704. His estate inventory deed lists the considerable property he left behind. It consisted of land and industrial facilities, such as a sawmill and a mill. The family’s home was located near the church, in other words, in the most prestigious area of the city. In addition, Jenderjan had several storage sheds in different cities where goods for sale, for example grain, were stored. The value of Jenderjan’s property was no less than 70,788 dalers. For example, a contemporary, alderman Daniel Pilcar, had 22 577 dalers and merchant Henrik Arvolander 37 736 dalers when they died. For ordinary mortals, the value of their property rarely rose above 1 000 dalers.

A huge amount of movable property is listed in the estate inventory: dozens of silver pints of different sizes, “tumlars” (drinking vessels), goblets and spoons. Most of them were finely decorated and marked with the abbreviation C.I.C.H.D, which includes the names of the spouses in the form Claes Ienderjan Charin Hinrich’s Dotter. It should also be said in this context that Jenderjan had quite a respectable number of books, around 200 volumes.

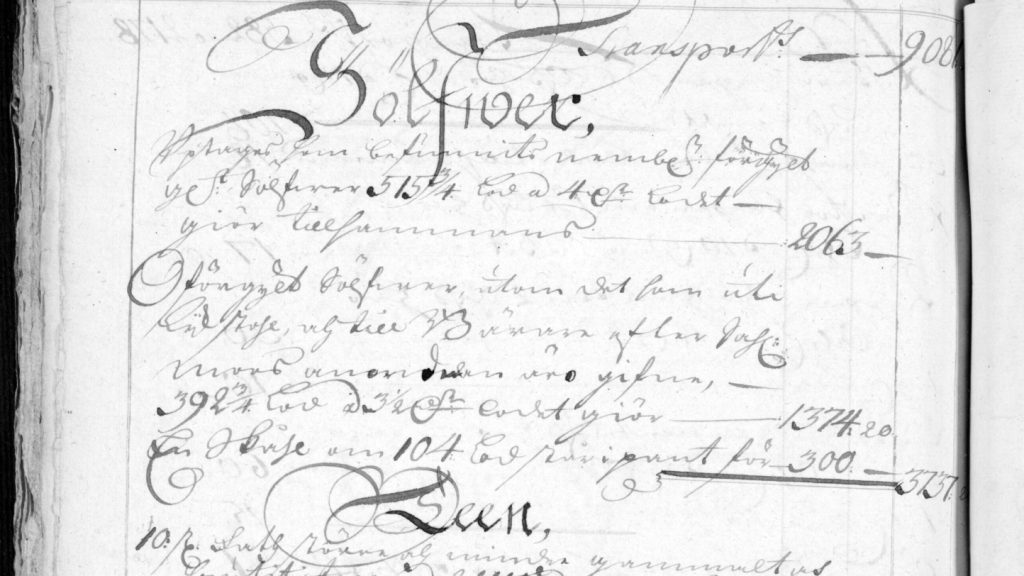

Katarina Heikintytär’s life was secured during the 33 years she lived as a widow after the death of her second spouse. The value of the widow’s property was 26,342 dalers in the estate inventory. Both Klaus Jenderjan’s and matron Jenderjan’s registers list a silver pint or “skål” weighing 104 lots (1,430 g). However, in 1737 it seems to have been pledged for the value of 300 dalers. Based on the weight, it could be this very same object that has now been acquired for the museum’s collections.

An exerpt from Katarina Heikintytär’s estate inventory, from the section where her silver estate is listed. The National Archives of Finland, Oulu, Oulun raastuvanoikeuden I arkisto. Perukirjat.

What is left of the Jenderjans’ inheritance?

What is left today of the wealth of the extremely wealthy family besides this jug? A crucifix that Katarina Heikintytär is said to have given for her husband’s coffin, is kept in the crypt of Oulu Cathedral. During the Great Wrath in 1714, the crucifix was transported to Sweden for safety, but it was returned to Oulu ten years later.

As a permanent memory of the story of Jenderjans’ wealthy family, there is a stone cellar located on the plot of the so-called Ynninkulma. The vaulted cellar is said to have been built by Klaus Jenderjan the elder, who came to Oulu from Germany in 1642. The marking “1656” found in the plastering of the vaulted cellar indicates the age of the structure. The basement is currently part of a building complex managed by Lapland Hotels Oulu. You can, for example, dine in the banquet room and feel the atmosphere of centuries past.

The stone cellar located at Kirkkokatu 3 was built in the middle of the 17th century. The building on top of it, on the other hand, dates from 1840. Photo: Picture archive of the North Ostrobothnia Museum / Ahti Paulaharju 1964.

NMKY’s (“Ynnin’s”) hall was demolished in 1988, and in the archaeological excavations of the site, a silver coin worth four marks from the era of Charles XI, dating back to 1693, was found. The coin probably slipped from the hand of Klaus Jenderjan the younger. The finder of the coin – Mika Sarkkinen, a student at the time and current museum archaeologist – describes the find: “I remember the moment of the discovery well. The discovery was made from the soil layer of the yard while digging “in situ” with a shovel. The coin was so valuable that we immediately suspected that Jenderjan had lost it.”

The impressive silver item is and remains in Oulu

Conservator of the North Ostrobothnia Museum, Marja Halttunen, has cleaned the jug. The gilded surfaces on the outer surfaces of the jug have worn away as a result of use and cleaning. The jug has probably been cleaned regularly during its history; there are residues of a paste used for cleaning in the engravings of the lid and in the grooves of the molded parts. As the paste gets older, it becomes difficult to remove because it is no longer very water-soluble, but it still corrodes the underlying metal. In addition, the white residue is unaesthetic.

The hardened cleaning paste was carefully removed mechanically with a wooden stick under the microscope and finally the surfaces were cleaned with a damp cotton swab. The outer surfaces of the jug have protective varnish in places, which has protected the jug from darkening. The inner surface has beautiful gilding that is in good condition and did not need any work.

Conservator Marja Halttunen has cleaned the jug. Photo: Inka Lohvansuu

Katarina Heikintytär’s morning gift has therefore traveled from Stockholm to Oulu and from Oulu back to Stockholm, to return here again in the 1720s. What happened to the jug after Katarina’s death in 1737 is shrouded in mystery. In any case, it was bought from southern Finland back to Oulu three years ago. And now it has returned within half a kilometer of the place where the home of the Jenderjans’ powerful family was located. The circle has closed.

The magnificent baroque object has been put on display in the museum’s main exhibition, where it can be seen until the end of the year, in other words, until the museum closes in Ainola. After that, the jug will be packed and stored to wait for the completion of the new main exhibition and its new appearance.

Authors: Curator Arja Keskitalo, Chief Curator Eija Konttijärvi and Conservator Marja Halttunen, Northern Ostrobothnia Museum

Sources:

The National Archives of Finland, Oulu, Oulun raastuvanoikeuden I arkisto. Perukirjat.

Alf Brenner, Oulun kaupungin perunkirjoituksia 1653–1750. Suomen sukututkimusseuran julkaisuja XXVI:1. Tampere 1953. Matti Enbuske, Jenderjan, Klas (1650–1704) suurkauppias, Oulun raatimies. Suomen kansallisbiografia. SKS 2004.

Pasi Kovalainen, Ynninkulman historia. Asein, aattein ja opein. Scripta Historica XXII. Oulun Historiaseuran julkaisuja. Oulu 1996.

Kirsi Schali, Kryptan krusifiksi, https://www.oulunseurakunnat.fi/kryptan-krusifiksi Interview with Archeologist Mika Sarkkinen 10.10.2023.